Programming GMP facilities has always been a challenging endeavor. Market uncertainties, limited process definition, and stringent regulatory requirements typically complicate the task. Too often, manufacturers end up with facilities that are underutilized or over capacity from day one. McKinsey & Company identifies Rightsizing Capacity and Greater Flexibility as two of the leading trends shaping the landscape of biopharma manufacturing today.

These are really two heads of the same coin, as both elements have a direct impact on facility utilization and cost of goods sold. Generally, facilities that are more flexible tend to be better utilized. But what kind of flexibility is most useful to achieve this utilization? And what are the challenges and trade-offs encountered when we implement new technology to achieve this flexibility?

Industry Insights on Facility Flexibility

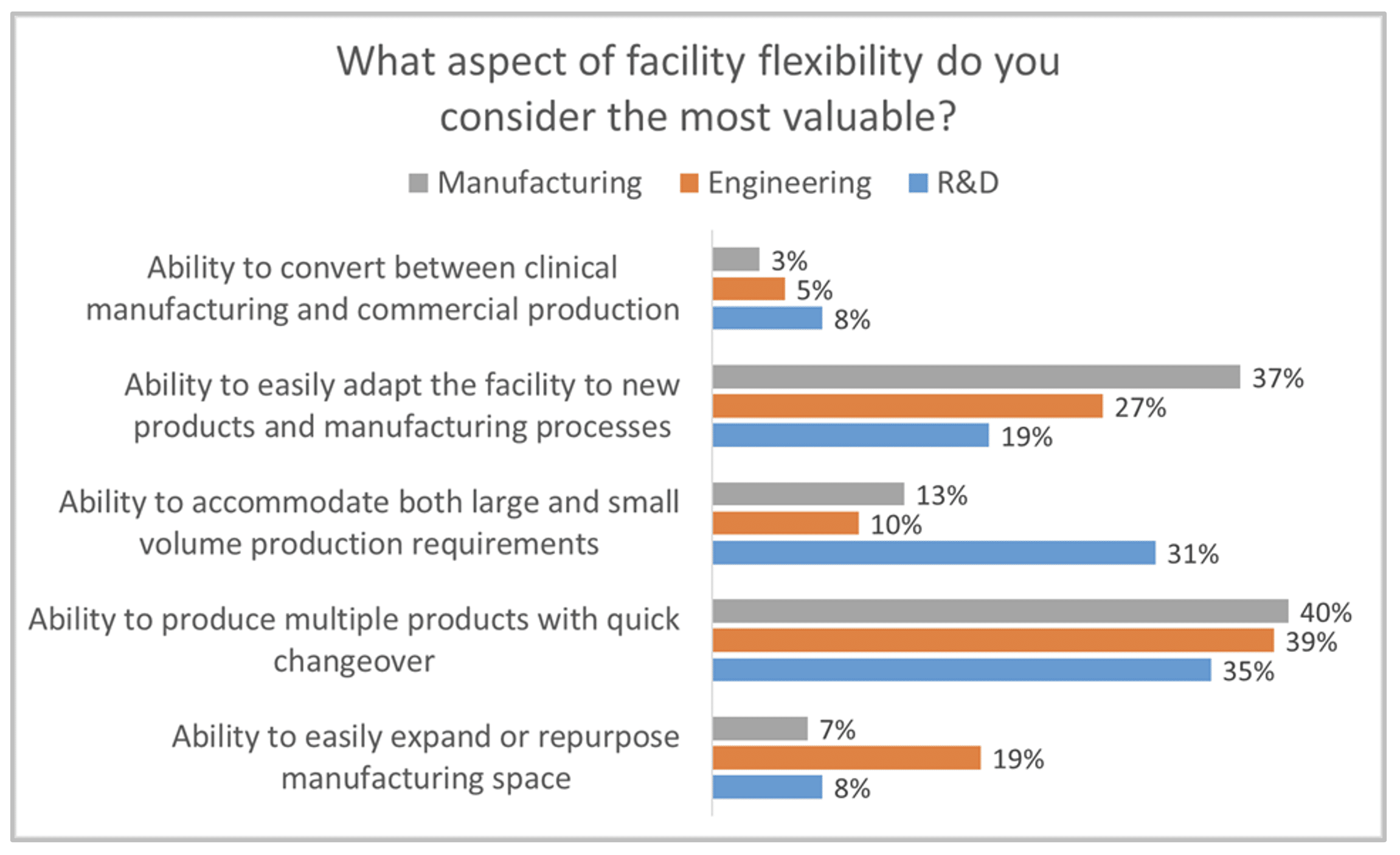

As part of Facility Focus, an industry-wide survey of the life sciences industry conducted by Carroll Daniel Engineering, in partnership with INTERPHEX, we asked industry insiders – those in engineering and operations roles – what aspect of facility flexibility is most valuable. Ranked from most to least valuable, participants responded as follows:

- Ability to produce multiple products with quick changeover

- Ability to easily adapt the facility to new products and manufacturing processes

- Ability to accommodate both large and small volume production requirements

- Ability to easily expand or repurpose manufacturing space

- Ability to convert between clinical manufacturing and commercial production

All of these elements are useful to maximize facility utilization, but overall multiproduct manufacturing with quick changeover is clearly valued the most. This held true even when we broke down responses by job function and affiliation. However, there were some notable differences in response when we looked at the secondary factors:

- Respondents in engineering roles significantly favored the ability to easily expand or repurpose manufacturing space.

- Respondents in manufacturing roles significantly favored the ability to easily adapt the facility to new products and manufacturing processes

- Respondents in R&D roles significantly favored the ability to accommodate both large and small volume production requirements

When you think about it these responses make sense because each survey cohort values the aspect of flexibility that is most useful in their role. This helps us to identify the most important aspects of facility flexibility to keep in mind when designing a facility. Traditional approaches to GMP facility design often tend to focus too early on physical attributes such as square footage or process scale as a function of single-product throughput. This approach neglects the foundational dialog regarding flexibility, proceeding on the assumption that all stakeholders understand and agree on the requirements for the facility.

Simply saying that facility flexibility needs to be maximized is inadequate. What is required is a better understanding of the types of flexibility that manufacturers need, from which we can more accurately develop facility designs tailored to the desired outcome. As applied to right-sizing facility capacity and building in flexibility by design, an in-depth grasp of the manufacturer’s business requirements and specific flexibility needs is essential.

Single Use Technology as Disruptive Innovation

The agent most frequently cited as enabling facility flexibility in the biopharmaceutical marketplace is disposables, or single use technology (SUT). This is because SUT conveniently allows manufacturers to outsource one of the most difficult aspects of multi-product bioprocessing – achieving process closure that fully segregates the product from potential sources of contamination, including cross-contamination from other products.

In so doing, it helps to realize the potential for licensed facilities to manufacture multiple GMP regulated products – a much more flexible paradigm. SUT also significantly reduces the time required for product changeover, effectively expanding plant utilization. Finally, SUT provides a tool for reducing the cost and complexity of facilities required for biopharmaceutical manufacturing. When applied comprehensively, SUT can lower the capital cost by reducing reliance on cleanroom environments to provide product segregation and eliminating the facility infrastructure required for clean-in-place and steam-in-place operations.

SUT is sometimes referred to as a disruptive technology. Yet there is nothing intrinsically disruptive about SUT. This is why Clayton M. Christensen, who first coined the term “disruptive technology,” now prefers the term disruptive innovation to describe this phenomenon. Christensen recognizes that it is the business model, not the technology per se, that transforms the marketplace. According to the Christensen Institute, “Disruptive innovation describes the process by which technology enables new entrants to provide goods and services that are less expensive and more accessible, and eventually replace—or ‘disrupt’—well-established competitors.” Disruptive innovation is further described as having three ingredients: an enabling technology, an innovative business model, and a coherent value network. The success of single use is an excellent case study in how these three elements need to come together in order to have a disruptive influence.

Like many enabling technologies, single use is surprisingly pedestrian. Those of us who grew up using Hefty bags to take out the trash can attest that there is nothing particularly innovative about the idea of disposable bags for bioprocessing. In fact, disposables were used in bioprocessing for over two decades before the technology began to be associated with the “facilities of the future” trend. One could argue that the development of 0.2-micron disposable sterile filters was a more intrinsically disruptive technology because it quickly enabled mammalian cell culture to displace microbial fermentation as the preferred commercial production platform for therapeutic proteins.

What single-use technology needed to become truly transformative was an innovative business model and a coherent value network. The Christensen Institute describes the type of innovative business model required as one that “targets non-consumers (new customers who previously did not buy products or services in a given market) or low-end consumers (the least profitable customers).” Further, “this is most easily accomplished by new entrants since they are not locked into existing business models.” The pharmaceutical industry provides a textbook example of this principle. Conservative big pharma was never going to be an early-adopter of SUT as a comprehensive business model. It was the small biotech firms – the 2nd and 3rd tier biomanufacturers for whom the cost and time required to build traditional facilities was a significant barrier to entry – these were the non-consumers for whom the “disposable factory” provided a new and viable solution. Top tier biopharm manufacturers studied SUT and tactically introduced the technology into existing biomanufacturing, but they didn’t make a strategic commitment to developing single use facilities until the business model was proven and they realized that they might be at a competitive disadvantage.

The final component, a coherent value network in which upstream and downstream suppliers, partners, distributors, and customers are better off when the disruptive technology prospers, is being realized today. The coherence of this value network is probably best illustrated by the rise of the Bio-Process Systems Alliance (BPSA) as a growing advocacy for single use. Founded in 2005, BPSA describes itself as “an industry-led corporate member trade association dedicated to encouraging and accelerating the adoption of single use manufacturing technologies used in the production of biopharmaceuticals and vaccines.” We now have a network of suppliers, partners, distributors, and customers who are significantly invested in making the single use facility of the future work. This will accelerate the transformative influence that it has on our industry.

Realizing the Benefits of Facility Flexibility

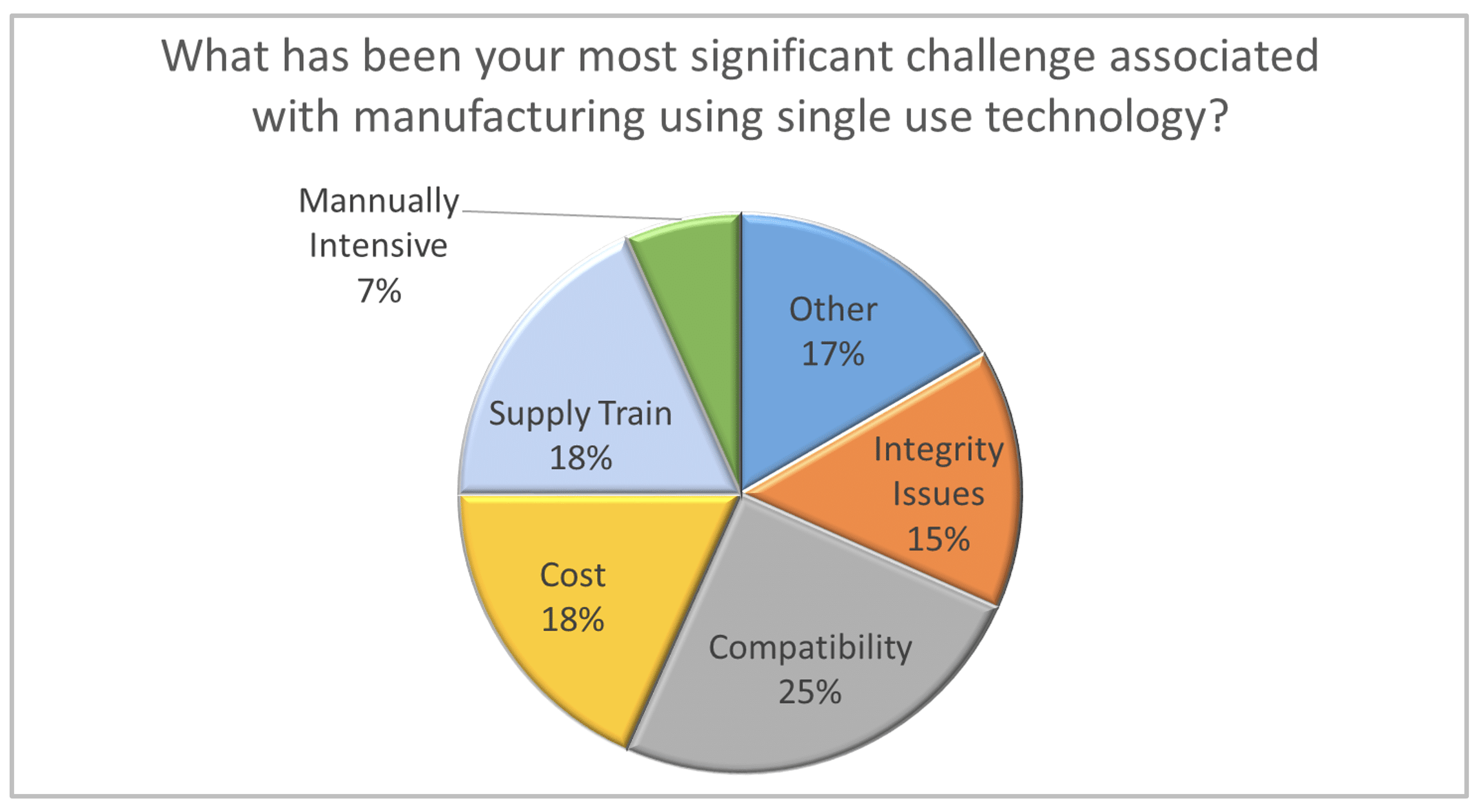

Recognizing that comprehensive single use biomanufacturing is a disruptive innovation, Shire and Biogen were among the first leading biopharmaceutical firms to use this business model to their competitive advantage. The subsequent adoption of the single use paradigm by big pharma validates the success of single use as a transformative influence in our industry. However, the introduction of new technology with a relatively immature supply chain in cGMP facilities is not without it’s difficulties. As part of Carroll Daniel Engineering’s Facility Focus survey, we asked biopharmaceutical

manufacturers to identify the most significant challenge associated with manufacturing using SUT. The responses revealed just how complex and dynamic this process is. While compatibility was cited as the most significant challenge, it was only a top concern for 25% of the participants. In addition, it is not clear if respondents were thinking in terms of compatibility with the process or compatibility between single-use components (i.e., a lack of industry standardization), so this response could be indicating two very different areas of concern. Several other issues prompted a double-digit response, including cost (18%), supply train (18%), and integrity issues (15%). A significant number of respondents (17%) indicated that their chief concern stems from other issues such as operator mindset, training, waste disposal and warehouse space for consumables.

Clearly, there is still much work to be done to realize the full potential of SUT to revolutionize biomanufacturing. It’s just as clear though, that the disruptive innovation genie is out of the bottle – leaving manufacturers scrambling to apply this technology in the most productive way. We’ve had a front-row seat for this industry transformation at Carroll Daniel Engineering, having assisted many manufacturers with the early adoption of single-use technology, the development of cGMP facilities designed to realize it’s benefits, and even the application of SUT for production of medical countermeasures by the US government.

We expect the trend to continue to transform biomanufacturing, and merge with other enabling technologies such as isolators and continuous processing, to develop facilities of the future that look very different from the established biomanufacturing network today. This will be coupled with innovative business models for the production of niche biopharmaceuticals, biogenerics, and gene and cell therapy, resulting in the development of a much more flexible and efficient manufacturing infrastructure in facilities of the future.

The Facility Focus survey has provided insight into the minds of industry insiders – those who have their share of war stories from experience with cGMP projects in legacy facilities. Our intent at Carroll Daniel Engineering is to continue the dialog, culminating in an updated and improved Facility Focus program at the next INTERPHEX.